BBY 5: Andor, Andor, and/or “And/Or”

The following is a drafty of a chapter from my book project on Star Wars: Andor. The plan was to have the book done before season two premiered. Given that season two debuts today, that’s not going to happen and I expect that a good deal of what I have finished will need to be rewritten. So I am sharing the work I have done, a sort of time capsule of my thinking on the show and on franchise more broadly.

Chapter 1

BBY 5: Andor, Andor, and/or “And/Or”

Andor begins with a low angle shot of lights set against a dark and stormy night (Figure 1). As the camera tracks from left to right, new lights appear and disappear. At first the appearances of these lights are punctuated by the score, but as the camera begins to pan to the right the lights and the music fall out of sync. As the camera continues to track and pan, a human figure becomes visible, walking parallel to the lights along a causeway towards a cityscape dimly outlined against the rain and the darkness. A cut to a second shot, at a lower angle, reorients the camera and the viewer. This shot focuses on the hooded figure’s legs set against a perspectival line opposite the one created in the first shot by the convergence of the lights, the causeway, and the camera’s movement. Rather than converging on a point in space ahead of this figure, this second, new perspectival line converges on a point behind him (Figure 2). Another cut presents a wider view of the causeway and the lights vanishing in the distance, of the figure who continues to move towards the vanishing point, and of the cityscape. This third shot offers neither forward nor backward movement but only a crane up that centers the vanishing point in the frame and positions the hooded figure just below it. As the camera settles in space and the shot concludes in time, a legend appears on the right side of the frame. The legend adds to the frame a second organizational scheme (the vanishing point being the first), one that divides it vertically into three unequal sections. The left hand section mainly contains the lights with which we began. The middle, and narrowest, section articulates the convergence of the lights, the street, the camera’s movement, and the hooded figure with the cityscape. The right hand section, again, contains three lines of text set against a darkness barely broken by the distant cityscape: “Morlana One/Preox-Morlana Corporate Zone/BBY 5” (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Andor Season 1, Episode 1 (00:01:07): Streetlight and street darkness.

Figure 2: Andor Season 1, Episode 1 (00:01:16): Legs, lights, and the past.

Figure 3: Andor Season 1, Episode 1 (00:01:34): The future and the past.

Taken together, these shots constitute for Star Wars a franchise image, a staging of tensions endemic to Star Wars insofar as Star Wars serves as a vector through which franchise contents move and within which they come to be ordered and reordered. Thus the three shots just discussed not only introduce Andor’s eponymous hero, Cassian Andor, the hooded figure. Through the image of light alternating with darkness, the first of these shots references one of the most fundamental aspects of the Star Wars franchise, namely the binary relationship between the sides of the Force. Insofar as Andor’s score synchronizes with the alternation of light and darkness before desynchronizng with this alternation, this shot suggests that Andor will not directly concern itself with such matters (and indeed it does not). The lights themselves, and the causeway to which they are attached, reference similar lights on Lothal, a planet that serves as a main setting for Star Wars: Rebels (Figure 4). Lothal, like Morlana 1, is under Imperial control. The appearance of these lights and this type of causeway in both series suggests an entire history of Imperial design, a way of organizing space on planets exploited by Imperial rule, and hence an Imperial political program far more nuanced than that suggested by, for example, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. The perspectival lines, and the tension between them, introduced in the first and second shots suggest Andor’s status as an “interquel,” as, on one hand, a sequel to what precedes it narratively (e.g. Solo: A Star Wars Story, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Star Wars: The Bad Batch) and a prequel to what follows from it narratively (e.g. Rebels, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, A New Hope) as well as, on the other, a sequel to what was released before it (e.g. not only Solo, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and The Bad Batch but also Rebels, Rogue One, and A New Hope) and as a prequel to whatever is released after it (e.g. The Madalorian’s third season, Ahsoka, and The Acolyte).

Figure 4

Salvaging Insurgency: Andor, Star Wars, and the Franchise Form explores such franchise images in order to make a particular claim about Star Wars and a more general claim about franchise and its historical conditions. In the first place, I argue that Andor develops and deploys two complementary forms of labor, salvaging labor and insurgent labor, through which it identifies potentially valuable franchise contents, abstracts those contents from their relations with Star Wars, and reorders those contents with each other in order to produce for and within Star Wars new values (e.g. new forms of heroic subjectivity, new forms of rebellion, new forms of critique) it has heretofore been unable to identify and develop for itself. In the second place, I demonstrate how these labor forms respond and contribute to an historical situation characterized by a scarcity of attention, a scarcity of the very capacity for reception and consumption required for an engagement with and intervention into franchise and a contemporary media ecology part and parcel of what McKenzie Wark calls “vectoralism.” In Wark’s account, vectoralism has succeeded capitalism insofar as the “dominant ruling class of our time no longer maintains its rule through the ownership of the means of production as capitalists do. Nor through the ownership of land as landlords do. The dominant ruling class of our time owns and controls information.”i This ruling class, the vectoralist class, exerts this control by way of owning the vectors—media platforms, network infrastructures, cultural products such as films and series, and so on—through which information flows. Vectoralism encourages the proliferation of information to the extent that such proliferation creates value. Salvaging and insurgent labor respond to this situation by granting to consumers, whether human subjects or franchise contents, the means by which to engage with and order information. They also contribute to this situation insofar as what orderings of information they produce are themselves information in need of further ordering.

In order to make these arguments in the chapters that follow, I will spend the remainder of this chapter laying their foundations. I first return to the franchise image with which I began in order to discuss how it “sets” Andor in relation to how Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope and the rest of the saga films “set” themselves through the legends with which they begin, Andor in a concrete, materialist manner and the saga films in a mythopoetic manner. This discussion of setting raises the question of how we should understand the relationship between Andor and the franchsie to which it belongs, whether the latter includes or excludes the former, whether the former seeks inclusion or exclusion within the latter. I argue that neither exclusion nor inclusion suffice to conceptualize what is, ultimately, and exclusive-inclusive relationship. As such, I posit the relationship between series and franchise by way of the conjunction suggested by the series’s title, “and/or.” This discussion reveals a second tension immanent to the franchise image with which I began, a tension over how Cassian Andor’s death in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story fits into the larger franchise narrative. What this death means and how it functions in that narrative depends upon whether one consumes it according to the release order of the texts that make it up (i.e. A New Hope, Rogue One, Andor) or according to the order established by the franchise storyworld’s internal chronology (i.e. Andor, Rogue One, A New Hope). Neither of these orderings, however, can be understood as natural or correct, as the multiple orderings offered through the Disney+ interface, and others produced by fans, demonstrate. Rather than offering a stable text with an ideally stable meaning, these orderings internally divide the texts they order and divide the external contexts in which these texts operate, proliferating new relations among these texts and contexts. These relations can be distinguished from the inclusive and exclusive relations implied by the “and/or” conjunction taken as two distinct functions, the “and” and the “or.” Insofar as they are relations among relations rather than relations among discrete, coherent objects, they can be expressed through “and/or” understood as a single, if internally heterogeneous, function. Establishing this function, finally, allows me to restate and add nuance to the overall argument of Salvaging Franchise: Andor and/or Star Wars before I offer a summary of the rest of the book.

To begin, then, consider the legend with which Andor’s opening sequence concludes. This legend defines the series’s initial “setting,” in both the conventional sense of the “time and place of the plot” and in the sense of the settings one adjusts on a device or machine to determine what it is capable of doing and how. As the viewer discovers over the course of the series’s early episodes, “Morlana One” refers to a planet in a free trade sector of the galaxy. “Preox-Morlana Corporate Zone” identifies a particular place on that planet and declares the power under which Morlana One operates, namely that of the Consolidated Holdings of Preox-Morlana Corporation, a sort of economic front for the Galactic Empire in the far-flung places of the galaxy (similar to the British East India Company).ii “BBY 5” sets Andor five years Before the Battle of Yavin, the latter the climactic battle of Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope during which Luke Skywalker destroys the original Death Star. The Battle of Yavin itself “sets” initial conditions for the entire franchise, as evidenced by the fact that all other events within the franchise narrative are understood in relation to that event. While the BBY/ABY system first emerged in the 1990s as a means to establish such relations between the original trilogy and what was called, at the time, the Expanded Universe, its appearance onscreen at the start of Andor marks its first use by a televisual or cinematic Star Wars text.iii

This appearance serves to both include Andor within Star Wars and Star Wars within Andor as well as to exclude each from the other. The saga films—the nine films the Skywalker story comprise—all begin with the same setting, “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…” That this legend is rendered in the same blue as “BBY 5” underscores inclusion, the fact that these legends emerge from a single origin, from a single inclusive “text” (i.e. Star Wars) and do similar, if rather abstract, work within each, namely establishing setting. By contrast, these legends underscore the extent to whichAndor and Star Wars exclude one another. “Morlana 1/Preox-Morlana Corporate Zone/BBY 5” sets Andor in a concrete place and time, a setting apposite the series’s materialist intervention into Star Wars. “A long time ago” sets the saga films abstractly in a non-place and a non-time apposite myth, apposite a story of heroes whose supernatural powers allow them to rise above their material conditions and re-set their worlds according to their desires (even if this re-setting never works finallyiv). As many critics have noted, the mythopoeisis associated with Star Wars can be understood as a reaction the New Hollywood Cinema that was dominant from the mid-1960s through at least 1977, the year A New Hope was released.v In this light, Andor engages with and intervenes into Star Wars by challenging the latter’s mythopoesis, one inaugurated: under historical conditions quite different than those that determined cultural production in 2022 (when Andor’s first season was released), by way of texts distributed through an altogether different medium (film vs. streaming television), and according to different assumptions about how texts should be “set.”

Thus we discover a key tension within this franchise image, one that relates this series to this franchise by way of an apparent antagonism having to do with how each sets for itself initial conditions that play determinant roles in how their respective plots unfold. However, my discussion of this tension suggests a second, one that is internal to Star Wars by virtue of being internal to Andor and one that becomes all the more complex by way of how it divides and complicates the franchise’s interiority and exteriority. Put simply, the exclusion I just described, according to which Andor and Star Wars relate to each other through their differences, only works to the extent that they also include one another. That is, the differences between Andor and Star Wars become visible only when they are set against an abstract sameness, a sameness that haunts Andor as it seeks to re-set Star Wars according to its materialist conception of the franchise. In other words, any distinction we make between the series and the franchise becomes indistinct once we recognize that Andor’s concrete, materialist setting always already and only exists in relation to the abstract, mythological one established in A New Hope. “BBY 5” could be read “Five years before ‘A long time ago…’”, hardly a particular, well-defined setting. If we take the Battle of Yavin as the zero-point for the Star Wars narrative, and when we recognize that this zero-point as part and parcel of a mythopoeisis (the making of a myth), we come to understand that every event that takes place in the franchise narrative takes place in relation to and under the auspices of that myth. At same time, that myth accrues value insofar as elements of the franchise (its various films, series, novels, comic books, video games, toys, and so on) relate themselves to that myth, that zero point, even if that relation is one of difference rather than resemblance.

As one of the franchise’s most heterodox texts, Andor would seem to relate to Star Wars by way of the “or” in “and/or,” which connotes exclusion. This exclusive relation affords our consideration of Andor in the context of its engagements with, for example, texts and contexts exterior to Star Wars, e.g. The Taking of Pelham 123 and Breaking Bad or New Hollywood Cinema and prestige television. At the same time, the Disney+ and Lucasfilm logos precede every episode of Andor, emphasizing the resemblance of series to franchise and suggesting that the each always includes the other (the “and” in “and/or”). This inclusive relation affords our consideration of the series’s engagements with the texts and contexts that make up Star Wars, e.g. Rebels and The Bad Batch or the mass of franchise paratexts such as the book Star Wars: 100 Objects or the Lego set Escape from Ferrix. While we might solve the dilemma implied here by way of a conscious choice—“I will consume Andor in its exclusive relation to Star Wars” or “I will consume Andor in its inclusive relation to Star Wars”—this solution reproduces a modern logic at odds with the series, with the franchise form, and with contemporary cultural production, as I shall discuss throughout this book. For now, suffice it to say that the exclusive “or” relationship, even if we merely prioritize it over the inclusive “and” relationship, implies the fungibility of one context with another. That is, while we might come to different understandings of Andor by consuming it in relation to Escape from Alcatraz or The Wire rather than Star Wars Episode VII: The Last Jedi or The Book of Boba Fett, we will in each case come to an understanding that can be productively compared to other understandings, an interpretation that can be productively compared with other interpretations, a critique that can be productively compared with other critiques. Each result (e.g. each understanding, interpretation, critique, and so on), operates individually, as a complete, coherent, meaningful or valuable product of the labor of a subject, whether a fan, critic, scholar, or similar. While each individual product differs from the rest, we can compare them in terms of their respective completeness, coherence, and meaning. As such, products, by way of a modern exclusive relation (they are different than but similar to each other), become commodities that operate according to an underlying sameness that allows one to be exchanged for the other in the same manner that one can exchange money for goods or goods for other goods.vi This modern logic understands commodities (and subjects) to be: discrete from one another, valuable in relation to all other commodities (or subjects), and complete and coherent when they confront the consumer (i.e. to already possess a value that the consumer consumes, even if the origin of that value remains obscure to the consumer). While this logic does account for the “labor” of consuming and understanding texts, it does not and cannot account for the labor solicited by the franchise form, salvaging labor and insurgent labor. These labor forms, like the form and the historical conditions to which they refer, dissolve the relations within and among modern subjects and objects and thereby clear the way for new relations and new value.

If we replace the exclusive relationship just discussed [“I will consume Andor in its exclusive relation to Star Wars” or “I will consume Andor in its inclusive relation to Star Wars”] with an inclusive relationship [“I will consume Andor in its exclusive relation to Star Wars” and “I will consume Andor in its inclusive relation to Star Wars”], we discover a different problem. Of course Andor must be, will be, consumed in relation to its many antecedents, with the many contexts in which it operates. However, even if we limit ourselves to the two contexts implied here, the context of the Star Wars franchise and the context of everything that is not of the Star Wars franchise, we find ourselves in the midst of an irreducible complexity insofar as these two contexts are themselves fully entangled with one another. For example, we might consume Cassian Andor as a revision of Han Solo—a consumption of Andor inclusive of Star Wars. By contrast, we might consume Andor as an engagement with Blade Runner, as evidenced by the rainy cityscape with which the series begins, a clear reference to the Ridley Scott film starring Harrison Ford whose condition of possibility includes the science fiction blockbuster originally known simply as Star Wars.vii In the first decades of the twenty-first century, everything that is not Star Wars exists in some inclusive relation to the cultural phenomenon called Star Wars. As such, “Star Wars” belongs to both sides of the equation. To consume Andor exclusive of Star Wars is already to consume it inclusive of Star Wars, both in the sense that specified non-relations can be understood as relations and in the sense that the totality of Andor’s exclusive relation to Star Wars (its engagements with the New Hollywood, with prestige television, with various film and television genres, with revolutionary politics, and so on) already and fundamentally includes Star Wars.

This inclusion spirals out of control, potentially incorporating everything and anything in the world in a double fashion. First, a discussion of Andor in its exclusive relation to Star Wars might address its take on realist or materialist science fiction engaged with labor politics, e.g. Alien or Snowpiercer. Second, this discussion will thereby also address, however indirectly, the fact that Star Wars itself helped to define the look of such films even if it did not address questions of labor. Ridley Scott has noted Lucas’s influence on the look of Alien and no comprehensive account of that film can avoid the fact that it (and the franchise it inaugurates) emerged in the wake of Star Wars. As such, elements of the non-Star Wars context with which Andor engages might be incorporated into our understanding of Andor in terms of that exclusive relation and then incorporated into that context again in terms of a meta-relation, the relation that the “exclusive” texts themselves have with Star Wars. Thus our new equation might read as follows: [“I will consume Andor in its exclusive relation to Star Wars” and “I will consume Andor in its inclusive relation to Star Wars” and “In consuming Andor’s exclusive relation to Star Wars I consume that exclusive relation’s inclusive relation to Star Wars” and “In consuming Andor’s exclusive relation to Star Wars and consuming that exclusive relation’s inclusive relation I consume that exclusively-relational inclusive relation’s inclusive relation to Star Wars”] and so on, to infinity.

This line of argument may seem either obscure or entirely obvious, but its importance cannot be overstated insofar as it speaks directly to the nature of the franchise form and the vectoralist political economy in which that form has emerged. The form of inclusion just described involves a potentially infinite extension as each new “and” adds another element to our consumption (e.g. The French Connection or the figure of the anti-hero in the 1970s) and another context in which that consumption takes place (e.g. the history of film or the history of the anti-hero). Moreover, each inclusion produces a tension between and within the various contexts, texts, and sub-texts of which Star Wars consists. That is, each inclusion divides the interiority and exteriority of franchise contexts, texts, and sub-texts, producing further contexts, texts, and sub-texts each of which might be exchanged as an individualized commodity and each of which might be further divided to produce new contexts, texts, and subtexts that might be further divided. When we perceive Cassian Andor as both Han Solo and Rick Deckard (and Popeye Doyle and Frank Morris and Walter White and Don Draper and…)—when we make use of our capacity for salvage—we no longer see him as an individual, as a complete, coherent, meaningful or valuable subject comparable with other such subjects. We see him as a dividual, a subject characterized by incompleteness, by internal divisions, by radical potential for both producing the new and reproducing the old, a subject apposite the political economy in which the franchise form has emerged. Likewise, this dividuation, “internal” to Andor and Andor, mirrors an “external” dividuation of Star Wars, the division of the franchise that produces new relations between the franchise and its internal relations, on one hand, and the series and its external relations, on the other.

Here we may return once again to the franchise image with which we began. To this point, I have described that image, and Andor itself, mainly in general opposition to Star Wars and in particular opposition to the saga films. While the materialism of “Morlana 1/Preox-Morlana Corporate Zone/BBY 5” excludes the mythopoesis of “A long time ago…”, it simultaneously includes Andor within Star Wars by setting the series in relation to Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, whose events take place immediately before those of A New Hope and thus immediately before the zero point of the the franchise timeline.viii Those events include the Scariff heist, during which the Rogue One crew steals the plans for the original Death Star and transmits those plans to the Rebel Alliance. Those events also include the deaths of every member of the Rogue One crew, including Cassian Andor. As of BBY 5, when Andor begins, this death lies in the future represented by the perspectival line produced by the convergence of the causeway, the lights, and the camera movement in Andor’s first shot. At the same time, as of 2022, when Andor’s first season was released, this death lies six years in the past, in 2016, when Rogue One was released. This past is represented by the second perspectival line introduced in the second shot. The obscurity of this line’s vanishing point, somewhere behind Cassian as he makes his way towards the obscure vanishing point that lies ahead of him, does not simply reference the fact the viewer as yet knows little of Cassian’s past (i.e. his life before BBY 5). It also represents Cassian’s ignorance of his own past, namely the past that is 2016, when he died. In short, he walks away from and towards his death at the same time. Surely, this contradiction merely derives from a confusion, a confusion between the internal chronology of the franchise narrative and the exterior history in which that narrative is produced and consumed (Figure 5). The mere fact that such a confusion might arise, however, suggests the difference between modern notions of the text and a contemporary account of contents, between a modern form such as the novel and a contemporary one such as franchise. As discussed above, novels have relatively clear boundaries and dates of publication. In other words, they are fairly stable texts that appear in fairly clear contexts. By contrast, the franchise form, especially massive instances of it such as Star Wars, effaces the distinction between text and context by way of the peculiar relations it produces among its contents and between itself and what seems to lie outside of itself. As such, does Andor appear in the context of what precedes it in time, i.e. Rogue One, in which Cassian Andor dies, and A New Hope, in which no one remembers that death? Or do Rogue One and A New Hope “appear” in the context of what precedes them, i.e. Andor as a series that tells the backstory (or simply the story) of this character?

| Narrative order The Acolyte (132 BY) Tales of the Jedi (~35 – 18 BBY) Episode I: The Phantom Menace (32 BBY) Episode II: Attack of the Clones (22 BBY) Star Wars: The Clone Wars (feature; 22 BBY) Star Wars: The Clone Wars (series; 22 – 19 BBY) Tales of the Empire (20 BBY – 0) Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (19 BBY) Star Wars: The Bad Batch (~19 BBY) Solo: A Star Wars Story (13 – 10 BBY) Obi-Wan Kenobi (9 BBY) Star Wars: Rebels (5 – 1 BBY; epilogue sometime after 4 ABY) Andor (5 BBY) Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (1 BBY) Episode IV: A New Hope (0) Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (3 ABY) Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (4 ABY) The Mandalorian (9 ABY) The Book of Boba Fett (4 ABY – 9 ABY) Star Wars: Resistance (34 ABY) Episode VII: The Force Awakens (34 ABY) Episode VIII: The Last Jedi (34 ABY) Episode IX: The Rise of Skywalker (35 ABY) | Production/Release/Consumption order Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (1983) Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999) Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005) Star Wars: The Clone Wars (animated feature film; 2008) Star Wars: The Clone Wars (tv show; 2008 – 2020) Star Wars: Rebels (2014 – 2018) Episode VII: The Force Awakens (2015) Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016) Episode VIII: The Last Jedi (2017) Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018) Star Wars: Resistance (2018 – 2020) The Mandalorian (2019 – ) Episode IX: The Rise of Skywalker (2019) Star Wars: The Bad Batch (2021 – 2024) The Book of Boba Fett (2022) Obi-Wan Kenobi (2022) Andor (2022 – ) Tales of the Jedi (2022) Ahsoka (2023) Tales of the Empire (2024) The Acolyte (2024) |

Figure 5: Ordering Star Warsix

Each of these orderings—the release order (i.e. A New Hope, Rogue One, Andor) and the narrative order (i.e. Andor, Rogue One, A New Hope)—excludes the other, an exclusion that has consequences for how consumers understand, interpret, and critique the franchise and its contents. Viewing these three contents in the order of their release allows us to see in and across them the movement of history external to Star Wars (from 1977 to 2016 to 2022) as well as the movement of Star Wars’s conception of itself as a franchise and as a narrative across that external history (e.g. from mythopoetic to materialist narrative). Moreover, the release order renders Cassian as a doomed figure, as someone whose present circumstances in BBY 5 present no real danger to him (we know he survives to BBY 1) by virtue of the future danger we know he cannot avoid. Viewing these texts in the order of the narrative they present allows us to see the movement of Star Wars’s internal history (from BBY 5 to 0) as well as the tensions among these texts’ respective understandings of their respective positions within the franchise (e.g. A New Hope as the mythical zero point and Rogue One and Andor as subordinate to the logic of that zero point). The narrative order thus presents Cassian as someone with a clearer arc, someone whose involvement in the Rebel Alliance is never a fait accompli, as it is mainly presented in Rogue One, but rather manifests by way of the characterization with which he begins (of a small-time hustler looking for his lost sister) becoming the condition for meeting Luthen Rael, for taking part in the Aldhani heist, to being imprisoned on Narkina-5, and so on presumably through the series’s forthcoming second season. Each of these readings, one based upon the historical release of franchise contents and the other on the franchise’s internal chronology, thus “sets” the contents in relation to one another and becomes a condition upon which any subsequent understanding of those contents must be based.

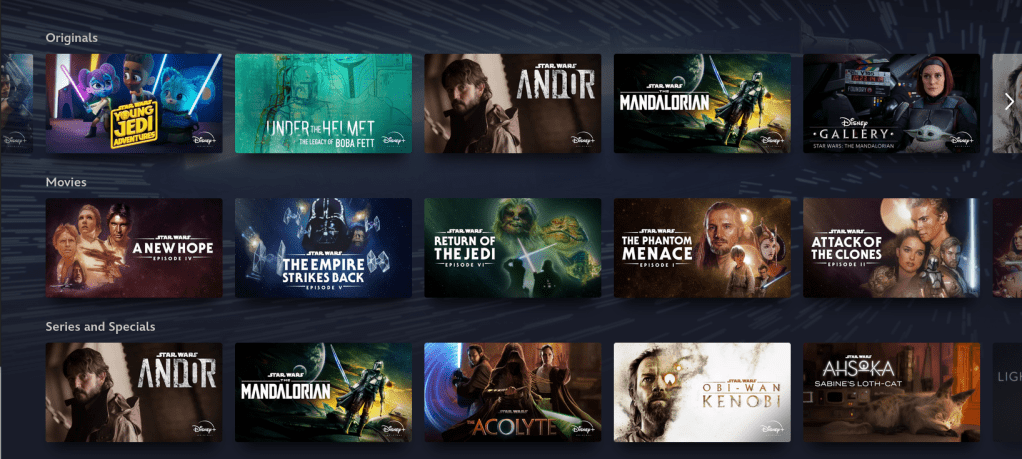

On one hand, the release ordering presents an obvious way through the franchise. One consumes each new franchise text as it appears and comes to an understanding of the franchise based on that consumption. On the other hand, in an era of streaming media and of the instant purchase (or, more accurately, licensing) of streaming content, the whole of Star Wars (or at least its televisual and cinematic contents) is available for consumption at any and every moment. In this context, the release ordering continues to make sense as a nostalgic engagement with franchise contents but now competes with an ordering naturalized by the Disney+ interface as “Star Wars in Timeline Order” (an ordering that includes all of the canonical Star Wars televisual and cinematic texts with the exceptions of Tales of the Jedi and Tales of the Empire). The same interface immediately denaturalizes this naturalization and demonstrates the dividual nature of the franchise and its elements by offering, as of this writing (16 June 2024) a total of ten orderings of the franchise: “Originals” (franchise contents produced for and released through Disney+), “Movies” (feature length films released in theaters, with the exception of Star Wars: The Clone Wars, which is excluded from this ordering), “Series and Specials” (seemingly everything but the movies and non-canonical narrative texts), “Star Wars Animation” (canonical and non-canonical animated narrative texts), “Obi-Wan Kenobi” (narrative and non-narrative texts about or including this character), “Documentaries” (non-narrative texts of the “making of” and “closer look” variety), the aforementioned “Star Wars in Timeline Order”, “Darth Vader” (narrative and non-narrative texts about or including this character), “Shorts” (short animated and non-animated, canonical and non-canonical, narrative and non-narrative texts), and “Star Wars Vintage” (mainly non-canonical animated texts and at least one text, the Clone Wars microseries, that was de-canonized to make way for The Clone Wars).

None of these orderings includes the entirety of the franchise’s televisual and cinematic narrative, much less the entirety of the franchise narrative (which would include other narrative contents such as canonical novels, comics, and video games) or the entirety of franchise contents (which would include non-narrative and/or non-canonical texts and paratexts such as non-fiction accounts of the franchise, toys, clothing, and so on). Along with the fact that none of them can account for the totality of the relations among the contents they do include, this fact demonstrates that every ordering of the franchise must be produced rather than assumed and that no ordering should be taken as superior to any other, whether it is sanctioned by Disney and Lucasfilm or created by consumers. The orderings suggested by Disney+ are merely that, suggestions. Because they should not and cannot be taken to be “natural,” the result of a neutral, mechanical process, they must each be understood as part of a single, ongoing process to establish new, sometimes unexpected relations among extant and emerging franchise contents—in short as part and parcel of the salvaging and insurgent labor in which Andor engages. Such labor, which produces both narrative and non-narrative relations among franchise contents, produces new value for Star Wars. For example, two of the first three Disney+ orderings, “Originals” and “Series and Specials, ” include Andor but relate it to the Disney+ service and to non-narrative and non-canonical aspects of the franchise (Figure 6). As such, they present the series in terms of a current and potential value to the franchise as content that might entice new subscribers to Disney+ or as bonus or extra material (a “special”)—all of which excludes (but nonetheless supplements) the series’s value as a progression or development of the story to which it seems to “naturally” belong. The other of these three categories, “Movies”, excludes Andor. This exclusion may seem obvious or natural, but such is the case only by virtue of a distinction between media (i.e. between film and streaming television) that Disney+ otherwise effaces. The constructedness of this ordering thus both emerges in tension with the affordances of the platform, affordances that allow for the sort of constructedness under consideration in the first place, and in concert with one understanding Star Wars’s value, namely one that associates it with the franchise’s cinematic excesses. The Star Wars: The Clone Wars feature does not participate in this excess, hence its exclusion from the ordering, although the fact that The Clone Wars series accounts for a plurality (approximately 30%) of Star Wars’s total run time suggests that any understanding of the films that gives them pride of place must be questioned.x Nonetheless, despite these complexities, insofar as “Movies” includes Cassian Andor (by virtue of Rogue One), the ordering salvages value from him as a character who relates to Darth Vader, to the Rebel Alliance, to the Death Star, and to the Force—to, in short, contents of Star Wars highly visible to a general public and thus contents of the franchise that already have great value. As dividualized contents of Star Wars, Andor and Cassian relate to the franchise in manifold ways, each of which produces value for the franchise that might be further developed through the production of still newer relations.

Figure 6

Because so many consumers of Star Wars likely consume it through Disney+, the service’s orderings of the franchise carry the weight of official sanction and offer to the consumer a sort of meta-stability. Nonetheless, the service does not have a monopoly on this process. Quite the contrary, as the labor of the consumer plays a vital role in producing other orderings and other relations and thus in producing additional value for the franchise. For example, the so-called “Machete Order” offers a way through the original and prequel trilogies that revises these films’ collective narrative as the story of Luke Skywalker coming to terms with his paternity while preserving the surprise with which that paternity is associated.xi To consume Star Wars in this ordering, one begins with the release ordering and views A New Hope followed by Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back, at the end of which one discovers that Darth Vader is Luke’s father. From there, one views Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones and Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith to understand how Anakin Skywalker became Darth Vader. In other words, what would be simply story were one to watch these two trilogies in narrative order becomes backstory, but a more calculated and perhaps meaningful backstory than the one that would result from watching the films in release order insofar as the two prequel films become both the story of Anakin Skywalker’s fall as well as the condition for Luke’s triumph over the dark side of the Force. (It should be noted that this backstory is perhaps less complete than the one that emerges through the release order as Rod Hilton, the creator of the Machete Order, does not believe Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace to be necessary in this ordering). Finally, with the knowledge of Anakin Skywalker’s fall in hand, one watches Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi and witnesses Anakin’s redemption and Luke’s triumph (all of which helps to explain the replacement of Sebastian Shaw with Hayden Christensen at Jedi’s conclusion). The Machete Order exemplifies how franchise value might accrue outside of the sets and locations, writers rooms, stakeholder meetings, and similar spaces associated with the culture industries and outside of the movie theaters, retail stores, and online spaces where consumption is understood as discrete from production. In other words, it provides one example of the salvage and insurgency, of the identification of value and the use of that value to dissolve old relations and produce new ones, that franchise fans enact by way of their attention to the franchise and the potential ways it might yet relate itself to itself.xii

All of my discussion thus far begins in the franchise image comprising Andor’s first three shots, an image in which we discover the tensions that animate Andor in relation to Star Wars insofar as Star Wars exemplifies an aesthetic form, franchise, that has emerged under conditions, those of late or post-capitalism, that challenge understandings of production and consumption that derive from modernity. To summarize my discussion of these tensions—over competing ways of setting Star Wars and among Cassian’s several pasts and futures—we should recall that the relationship between Andor’s materialist setting and the saga films’ mythopoetic setting cannot be adequately explained by way of inclusion or exclusion. Both the inclusive and exclusive relations described above rely on abstraction and the concrete. The inclusive relation assumes that Andor and Star Wars belong to the same franchise, if for no other reason than they both can be consumed through Disney+’s Star Wars section. It also relies on the fact that, despite the very different forms of setting they suggest, “Morlana 1…” and “A long time ago…” nonetheless do the same work, that of setting franchise narrative contents. The exclusive relation described above depends upon our understanding of Andor and the saga films as being distinct from one another, a distinction reinforced by another distinction, between the series’s materialist revision of Star Wars and the saga films mythopoesis. These relations serve as adequate starting points for viable readings of the series in relation to the franchise according to a modern image of consumption, in which distinct products (here the readings based on one relation or the other) might be compared by way of their underlying sameness, by virtue of the fact that they are both readings. However, once we recognize that our capacity to choose between these readings and their respective conditions depends upon their entanglement with one another—on the fact that Andor’s materialist setting operates in relation to the saga films’ mythopoetic setting or on the fact that Cassian Andor’s complex temporal position depends up the complex relation between the franchise’s release ordering and its narrative ordering—we must also recognize the limits of this approach with regard to the franchise form and with regard to the historical conditions under which it emerges.

If exclusive and inclusive relations, as described here, prove inadequate to the franchise form and its historical conditions, such is the case because they assume that what they relate are texts, individuals, or commodities—objects that exist independently of the relations between them as discrete but comparable entities. It makes little difference if these objects relate to one another through similarity and inclusion or through difference and exclusion. In the end, they remain themselves regardless of how they are ordered. However, as I argued above, the relations established among franchise contents, whether in the context of production or of productive consumption, do not simply join those contents to one another, nor do they simply distinguish such contents from one another. They divide these contents internally. The division of texts produces sub-texts, which in turn become texts. Individuals become dividuals, which are further dividuated. Commodities give way to more commodities, as when Andor’s third episode (packaged together with the first two as a means to sell the series to Star Wars fans and potential fans, divides and, in so doing, produces the Escape from Ferrix Lego set, a non-obvious toy that nonetheless adds value to the series and the franchise in a manifold manner. This sort of “internal” division has an “external” counterpart, as each division of franchise contents also proliferates the contexts in which which those contents relate to themselves and to the contents of other cultural productions. Thus the cityscape Cassian Andor approaches, reminiscent of the decaying urban environment of Blade Runner, produces a second context in which to understand the series and Star Wars itself beyond the initial context provided by the latter, namely the history of science fiction cinema. Each division thus suggests new relations among the contents and contexts so produced. Thus Andor, Rogue One, and A New Hope each relate to Cassian Andor as alive and Cassian Andor as dead, to a franchise ordering in which he will die and to a franchise ordering in which he is already dead, at the same time. Insofar as these orderings themselves involve first and foremost relations produced through the productive consumption of salvaging and insurgent labor, it would be inaccurate to say that the relations among these texts and Cassian are relations among discrete things. Rather, they are relations among relations.

Here the many strands of the present discussion come together. To understand Andor and Star Wars as being determined by “relations among relations” is to understand the texts, sub-texts, and contexts that make up the series and the franchise in terms of dividuality rather than individuality, a shift that demands new concepts and vocabulary. These dividual texts, sub-texts, and contexts can thus be designated as the content, or better contents, of the franchise form. If a text is a delimited, coherent whole (ideally, at any rate), if a sub-text is some part of that whole distinct from other such parts, if a context is an environment or space in which texts and sub-texts operate in relation to other texts and sub-texts understood to also be delimited, coherent wholes, then a content is the same entity understood as information in the sense that Wark gives the term, as what “expresses the potential of potential. When unfettered, [information] releases the latent capacities of all things and people, objects and subjects.”xiii That is, franchise contents, understood as informational rather than textual, produce and participate in manifold and irreducible internal and external divisions that, through their taking place, afford new relations and new value. The franchise image becomes, in this argument, merely a highly visible and fraught instance of the tensions that run throughout franchise contents. However, Wark cautions us that the potential of information, what I am calling the relationality of relations among franchise contents, poses a danger: “When information is not free, then the class that owns or controls it turns its capacity toward its own interest and away from information’s own inherent virtuality,” away, that is, from its potential.xiv As such, just as we cannot simply choose to consider Andor and Star Wars inclusively or exclusively, according to an “and” or an “or,” or even according to an “and/or” understood to involve two discrete forms of conjunction, we cannot choose to investigate franchise and contents as serving the new or as serving the old, as serving revolution or as serving counter-revolution. We must investigate both at the same time, by way of an “and/or” understood as a single function that, by virtue of the inclusive-exclusion and the exclusive-inclusion it connotes, is itself dividuated.

As an aesthetic form characteristic of the twenty-first century, franchise signals a transformation in the how culture is produced. No longer do we consume complete, coherent texts that might be distinguished from one another and, through such distinction, be exchanged for one another. Rather, we consume contents. Sometimes a content, such as the series Andor or the film A New Hope, appears to be a text, but a content might also be a character, a plotline that runs through any number of “texts,” an image, a bit of music, or a camera movement. Likewise, Star Wars itself is a content, as is the New Hollywood cinema, prestige television, and the totality of culture. Franchises proliferate contents. That is, they enact, and solicit from consumers, salvaging labor, which identifies the value of such contents in order to actualize new relations among them, and insurgent labor, which dissolves old relations in order to clear the ground for the new. Insofar as every content is always already the actualization of relations among contents, salvaging and insurgent labor operate upon a manifold relationality of relations that serves as both the condition for the new and for the reification of established power structures. This new situation demands a new method of analysis, one with the capacity to consider and interpret this relationality and the proliferation of contents it involves. Only by developing and deploying such a new method can we discover how the franchise form operates and, in turn, the nature of twenty-first-century cultural production. Salvaging Insurgency: Andor, Star Wars, and the Franchise Form endeavors to begin this process.

We left Cassian Andor in a state of suspension, caught among several pasts and several futures, alive and dead and/or alive or dead. His very name bespeaks this suspension. “Cassian” derives from the Latin “Cassius,” which translates as “vain” or “empty.” Insofar as Cassian cannot escape from his past death or from his future death, everything he does seems to be in vain. Insofar as he spends much of the series that bears his name not using that name, and insofar as he must hollow himself out before he can commit to the Rebellion, he appears as an empty shell, a form waiting for its contents characterized by a dividuation announced by the series title card (Figure 7). There, Cassian’s last name is stylized such that the spatiality of the “O” in “Andor” is inverted, the bowl of the letter represented as negative space and the counter as positive space, the latter resembling the “/” in “and/or,” a division that also joins, an exclusion that also includes. From this relationality, what insurgency might we salvage?

Figure 7

iMcKenzie Wark, Capital Is Dead (London ; New York: Verso, 2019), 5.

iiI adopt here Gerry Canavan’s approach to citation in the context of franchises with massive fandoms.

iiiThis dating system emerged in the 1990s as an external means to situate what was then known as the “Expanded Universe” (e.g. the novels Heir to the Empire, Dark Force Rising, and The Last Command) in relation to the narrative presented in the original trilogy. After Disney’s 2012 acquisition of Lucasfilm, it was referenced in canonical texts that were nonetheless only indirectly part of the franchise narrative. Star Wars Workbook and Atlas https://starwars.fandom.com/wiki/%27ABY-BBY%27_dating_system. Note that, as of the release of Star Wars: Timelinesin 2023, the date of A New Hope and the Battle of Yavin is simply given as “0.” No other franchise texts, not even Rogue One or the final season of Rebels (the former of which directly precedes and the latter of which intersects with the events of A New Hope).

ivSee gerry’s article on Force Awakens

vexamples

viThis is Marx’s C-M-C formula, by which commodities are transformed into another, abstract commodity (money), which is, in turn, transformed back into a commodity. In this fashion, all commodities can be exchanged with one another by way of a a single commodity (again, money) that renders them equivalent to one another.

viiThe resemblance of Andor to Blade Runner and Cassian to Rick Deckard in particular is underscored by the similarity of these characters’ respective sidearms.

viiiDiscuss: https://starwars.fandom.com/wiki/0_BBY

ixThis table includes all canonical televisual and cinematic texts as of June 2024. The column representing Star Wars narrative order includes dates only for already released texts so it does not include, for example, dates for Andors second season, which is rumored to take place from BBY 5 – 1.

Other franchise texts include:

- The 100+ novels and other books that were considered canonical before Disney acquired Lucafilm in 2012. The most famous of these are Heir to the Empire (1991), Dark Force Rising (1992), and The Last Command (1993),p—the Thrawn which tell the story of what happened to the Empire and the Rebellion after Return of the Jedi, a story that is replaced by the sequel trilogy (Episodes VII – IX). These titles were rebranded as Star Wars Legends after the acquisition, rendering all of the stories they told non-canonical, although some characters and plotlines have been recycled from them, notably Grand Admiral Thrawn in Rebels and Ahsoka.

- The 1978 novel Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, which was was written as a potential sequel to A New Hope in case the film did not perform well. It therefore may have been canon in 1978 but was replaced by The Empire Strikes Back upon its release in 1980.

- The numerous novels and collections of short stories that written since Disney’s acquisition of LucasFilm.

- Numerous comics series that also became Legends after the acquisition as well as some comic series still being written that are considered canon.

- Episodes IV – VI were dramatized for radio from 1981 – 1996. As adaptations, their canonical status is somewhat moot, but they do offer bits of lore not found in the films (including the first use of the word “Sith,” a term never used in the original trilogy).

- Some Star Wars video games may include canonical elements (“true” bits of story or information provided nowhere else).

- Various paratexts (especially the toys) may also provide canonical information even if they do not participate directly in the narration of the canonical franchise story.

- Other texts, such as The Star Wars Holiday Special (1978), Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure (1984), Ewoks (1985 – 1986), and Droids (1985 – 1986) are considered non-canonical or have dubious relations to canon.

xSee https://blog.swgediscord.com/how-long-is-star-wars/ These totals do not include Tales of the Empire or The Acolyte. The total run time, in minutes, is 10,923. The Clone Wars accounts for 3261 of those minutes, or 29.8%, higher than all of the films combined. The next highest percentage of the total run time comes from Rebels, which accounts for 1706 minutes, or 15.6%. The films, in total, account for 1617 minutes, or 14.8%.

xihttps://www.rodhilton.com/2011/11/11/the-star-wars-saga-suggested-viewing-order/

xii Other examples include large scale, nearly industrial projects such as Project 4K77, Project 4K80, and Project 4K83—each of which seeks to restore one of the films from the original trilogy to its release condition, in defiance of the changes to those films Lucas made with the 1997 special editions—as well as smaller projects such as the so-called “Phantom Edit,” which re-cuts The Phantom Menace to remove all traces of Jar Jar Binks, and “What if ‘Star Wars Episode I’ Was Good,” which takes the elements of that film and re-imagines how they come together into a narrative. See https://www.thestarwarstrilogy.com/project-4k77/, https://www.thestarwarstrilogy.com/project-4k80/, and https://www.thestarwarstrilogy.com/project-4k83/ as well as https://archive.org/details/phantom-edit as well as https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgICnbC2-_Y

xiiiMcKenzie Wark, A Hacker Manifesto (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), para. 128.

xivWark, para. 129.

xvMcKenzie Wark, Capital Is Dead (London ; New York: Verso, 2019), 5.

Leave a comment