A place where time stands still: Prehistory and/or Posthistory

The following is a drafty of a chapter from my book project on Star Wars: Andor. The plan was to have the book done before season two premiered. Given that season two debuts today, that’s not going to happen and I expect that a good deal of what I have finished will need to be rewritten. So I am sharing the work I have done, a sort of time capsule of my thinking on the show and on franchise more broadly.

Chapter Two

A place where time stands still: Prehistory and/or Posthistory

We left Cassian Andor suspended between past and future, between past life and future life, between past death and future death. More precisely, we left Cassian suspended among and within the complex relationality of manifold pasts and manifold futures. Cassian does not walk away from a past or towards a future, nor does he walk away from a future and towards a past. He walks away from a past in which he had a sister, in which he searches for his sister, even if this past will only be recounted in a future towards which he is walking. He walks away from a past in which he has already died even as he walks towards a future in which he has not yet to died but will. He walks away from a past in which he has been forgotten even as the actions he is about to take will become the condition of that forgetting.

While these pasts and futures may be ordered in any number of ways, none of those ways will be superior, more natural, or more original (in the sense of “providing an origin or point of commencement”) than any other. Whatever claim we might make about the best or proper ordering of these pasts and futures must confront competing claims with no more or less authority than our own. We might, for example, after having completed Andor, and with full knowledge of the films that precede it historically, produce an ordering according to which Cassian has already died (in 2016) by the time the series premiers (in 2022). This ordering dissipates any narrative tension with regard to the question of Cassian’s survival, but it expresses a certain tonal intensity, a sense of doom that colors all of his actions in the series. By contrast, we might produce an ordering according to which Cassian’s fate remains unknown, the actions of the series (set in BBY 5) preceding the events of Rogue One (set in BBY 1). This ordering expresses the narrative tension just described but excludes the tonal intensity. Each of these orderings is rectilinear in one manner or another. The former involves an historical rectilinearity (grounded in the release order of franchise contents) that begins with Cassian’s murder of Tivik in Rogue One and moves through his death at the end of that film and thus onto the events of Andor. The latter involves a narrative rectilinearity (grounded in Star Wars’s internal chronology) that begins with young Kassa on Kenari and proceeding through his incarceration, his search for his sister, his flight from Ferrix, and so on unto his death on Scariff. Such rectilinear orderings would stand in contrast to orderings that mix narrative and history and thus produce circularities, spiralarities, and other topologies without names, especially insofar as these other orderings might involve other franchise contents, whether narrative and canonical or otherwise. What prevents us from starting our narrative with the scene in Rogue One when Cassian first appears onscreen with Mon Mothma before proceeding to a “flashback” that identifies the senator as the character who first appeared in Return of the Jedi discussing the many Bothans who died delivering news of the second Death Star to the Rebel Alliance and then onto a “flashforward” that recounts the individual journeys that Mon and Cassian take, in Andor,to the Rogue One scene, all intercut with scenes from films, series, and other media relating to the design, development, deployment, and destruction of the several Death Stars that populate the franchise? In short, nothing but the prospect of the non-trivial amount of labor it would require to produce and consume this ordering.

Such an exercise as this of course solicits discussions about and arguments over objective facts and subjective interpretation, matters that concern any number of types of consumers, including the fan and the scholar. Such discussions and arguments arise, as I shall demonstrate, in the context of an obsolete understanding, a modern understanding that takes franchise as a production model or logic in the service of producing narratives of a similar sort as those offered by the novel, by the standalone film, or even the television series. The franchise form must be distinguished from these other narrative forms insofar as those forms assume a degree of coherence that franchise cannot, indeed a degree of coherence that franchise does not even desire. Those older forms achieve their manner of coherence by way of their relatively stable boundaries (the covers of a novel, the run time of a film) and by way of their participation in what Jean-François Lyotard calls a grand or meta-narrative, a narrative that provides the condition of sameness through which disagreement, difference, progress, and so on might be understood and expressed.i Even under the condition of postmodernity, when, Lyotard argues, people have become incredulous of grand narratives, there remain those individual texts, such as A New Hope, that express a desire for grand narratives and the relatively clear distinctions (between, for example, good and evil) they afford. However, as I shall discuss in more detail below, Hiroki Azuma argues that our incredulity towards grand narratives produces a new form of credulity, a belief in nonnarrative.ii Azuma should not be misunderstood as arguing that narrative has no place in the twenty-first century. Rather, he argues that the “small” narratives valued by contemporary consumers do not subordinate themselves to grand narratives that, insofar as they collectively order the small narratives, allow for hierarchization and other forms of comparison according to which small narratives (what I have referred to as “orderings”) might be judged as superior or inferior in relation to one another. These small narratives, in the absence of the superior ordering force of the grand narrative, are a result of the labor involved with a consumer’s interaction with the atomistic elements of a given cultural production that might participate in narrative but must be distinguished from narrative properly speaking. In Azuma’s discussion, these elements are those that anime images comprise, such as big socks, certain eye shapes, or animal ears. In the present context, these elements are the contents—such as films, series, shots, components of shots, characters, real and imagined objects, paratexts, toys and other paratexts, and so on—out of which orderings of Star Wars are produced. As such, Azuma identifies a shift in contemporary culture from the consumption of narrative to a consumption of the database.

The present chapter sets up my discussion of this culture and its form of consumption in chapter two by way of an investigation of the long process of abstraction that led to this state of affairs. Here I address Star Wars as a place where time stands still, as a place where history does not and cannot operate according to conventional understandings of it. Vilém Flusser’s discussion of traditional and technical images helps to not only shed further light on the nature of the franchise image. Through its articulation of the traditional image with prehistorical myth and the technical image with posthistorical calculation, it also clarifies the nature of this place where time stands still. This discussion gives way to a consideration of a second franchise image, one that juxtaposes artifacts from the history of Star Wars with one another and thus presents an image that seems to be traditional, and therefore mythopoetic, but is rather technical, and therefore “content-poetic.” However, insofar as this image presents and produces contents, it appears to participate in an historicizing operation internal to Star Wars, an appearance that must be addressed and dismissed. A discussion of Fredric Jameson’s influential reading of Star Wars as a nostalgia film and the historicist methodology through which he produces this reading then serve to clarify the posthistorical nature of the franchise form. Historical forms such as the novel and the film participate in and deploy multiple, often contradictory codes within their individual instances and across the totalities of those instances (i.e. across the entirety of the form). These codes, and the metacode that unifies them into a consumable discourse (i.e. history itself), carry with them assumptions about the nature of the individual text and about the world that produces individual texts that cannot be reconciled with the franchise form or the world in which it emerges. This argument in hand, I offer a reading of our second franchise image by way of Azuma’s theorization off nonnarrative, a reading that demonstrates the extent to which metacodes and grand narratives no longer provide contexts in which meaning might emerge through narrative forms. Rather, under posthistory and under the regime of the technical image such metacodes and grand narratives become more contents. This reading further reveals the conflicted relationship between Star Wars and Andor, the degree to which the series constantly insists on its narrative as the material ground for the mythopoesis of the saga films, a material ground that nonetheless constantly disappears in the ordering and reordering of franchise content.

Vilém Flusser begins Into the Universe of Technical Images by describing the co-evolution of the human and techniques of abstraction. For Flusser, the human animal, by virtue of the actions of its hands, emerges from a four-dimensional, self-similar, unalienated existence by grasping elements of the world it inhabits. In the wake of such action, “the lifeworld falls into two areas: the area of the fixed, understood object and the area of the ‘one who understands, the human subject standing apart from objects.’”iii This process reduces human existence to three dimensions. The world becomes one of graspable objects that may be ordered by the subject into culture. When humans begin to coordinate the action of the hand with the vision of the eye they take a second step up the ladder of abstraction. At this level, the human begins to imagine, to see the world as a series of two-dimensional, traditional images. Such images, which relate the elements of the world to one another according to human thought and desire, are distinct from the isolated three-dimensional objects the human grasps and rips from nature. Flusser describes these images as standing between things and the human. To return to those things from which it has been alienated, the human must take another step up the ladder and abstract from the image concepts that help the human understand the objects represented in the image and their relationships with one another. At this level of abstraction, history, in the proper sense of the term, emerges insofar as what had been a four-dimensional world has been reduced to a single, linear dimension, i.e. writing and other symbolic codes. Writing affords meaning (of images, whether in material form or simply imagined) and thus the sort of exchange I briefly discussed in my introduction. A final abstraction leads to the technical image, whose emergence becomes necessary when texts become unreadable, when texts “collapse into particles that must be gathered up,” when we must calculate with the elements of texts we no longer understand.iv

Flusser’s work on this topic becomes crucial in the present context insofar as he implies that the age of linear texts, the historical age, the human age in the most precise sense, must be understood as an aberration, a brief period of relative rationality set between two different regimes of the image, one prehistorical and the other posthistorical, one dedicated to the truthful presentation of what is and the other to the production of what is not (yet). Flusser extends this line of thinking in a key passage, worth quoting at length:

The universe of traditional images is a magical and mythical universe, and if it nevertheless changes constantly, this was through unintentional coincidence, by accident. This is a prehistoric universe. Only since linear texts appeared, and with them conceptual, historical consciousness—some four thousand years ago—can one rightly speak of a history of images. For only then did imagination begin to serve (and oppose) conceptual thinking, and only then did the image makers concern themselves with being original, with deliberately introducing new symbols, with generating information. Only then was an accident no longer an oversight but rather an insight. Images of our time are infected with text; they visualize texts. Our image makers’ imaginations are infected with conceptual thinking, with trying to hold processes still.v

During the four thousand year period of history properly so called, texts strung concepts together along a single axis, along a line that disappears according to the final abstraction that leads to the technical image. Concepts are themselves abstractions of traditional images, descriptions of what traditional images imagine out of the three dimensional world of graspable objects, descriptions and expressions of the relations among the elements of a given traditional image. The technical image begins with the abstract concepts produced by texts and attempts to visualize those concepts in relation to one another. Subjectivity plays an increasingly important role at each stage of, even as it is transformed by, this process of abstraction, first imagining two-dimensional relations among the objects of a three-dimensional world, then conceptualizing one-dimensional relations among the elements of traditional images, and finally calculating zero-dimensional relations among textual concepts. Thus subjectivity, through its imagining, its conceptualizing, and its calculating/computing, introduces the new into the world, albeit in different ways. The prehistorical, premodern subject, under the regime of the traditional image, sought fidelity with the world it imagined, sought to minimize the newness introduced by its actions. The historical subject, the subject of history and of modernity, sought to balance tradition with novelty, sought to maintain the forms through which concepts passed with the novelty of such concepts understood as content (but not yet contents). The postmodern, posthistorical subject confronts a world in which there seems to only be the new, a zone “flooded with shit” to anticipate my discussion of posthistorical sign systems in chapter four. The technical image constitutes, then, a last ditch effort to arrest and make sense of the constant emergence of the new, to re-establish a form that might make sense of contents (which are no longer content), to stop the flood of shit. However, after the shift from narrative consumption to database consumption has been completed, as per Azuma’s argument, this flood cannot be stopped.

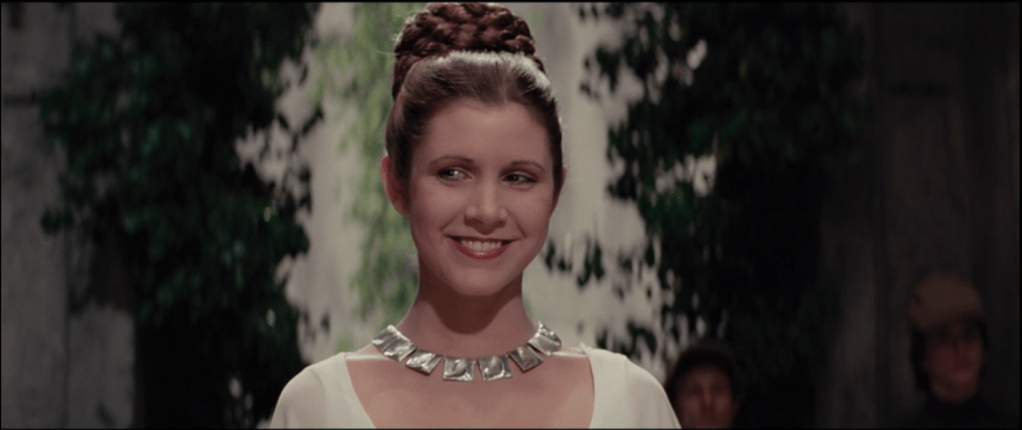

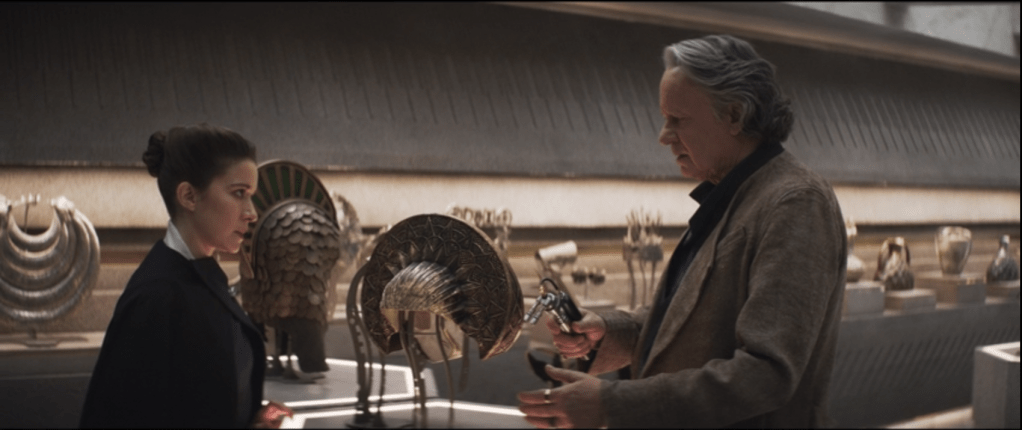

Andor’s fourth episode, “Aldhani,” provides a second franchise image, one that visualizes the tension between pre- and posthistorical thought, a tension that exists between Star Wars’s mythopoetics and Star Wars’s content-poetics, in the form of Luthen Rael’s antiquities gallery. We first encounter this gallery, which serves as a front and hub for a rebel network, after Luthen delivers Cassian to Aldhani and to the cell led by Vel Sartha as it prepares to heist an Imperial payroll. Upon returning to Coruscant, the ecumenopolis that serves as the galaxy’s capital, Luthen temporarily discards his identity as a coordinator of rebel activity and adopts the persona of a privileged dandy before appearing within the space that necessitates this transformation. The first scene set within the gallery sees this transformed Luthen entertain Senator Mon Mothma, one of the few characters from the Star Wars films to appear in Andor and, as suggested above, one of the contents consumers might order as they produce new relations within the Star Wars database (Figure 1). As she enters the gallery, Mon apologizes for her lateness, caused by a busy and stressful morning. Luthen replies, “Free your mind, senator. This is a place where time stands still.” The gallery, which emerges as a franchise image across multiple episodes of Andor, expresses this timelessness through a well-lit, nigh transparent juxtaposition of objects, many of which, upon inspection, reveal themselves to be contents of the Star Wars database. As Luthen, Mon, concierge Kleya Marki, and chauffer Exmar Kloris move about the space (in “Aldhani” and in subsequent episodes), we discover, among other things: Mandalorian armor suggestive of Boba Fett’s armor in the saga films as well as of the armor worn by various Mandalorians in Star Wars: The Clone Wars, Star Wars: Rebels, and The Mandalorian; a headpiece reminiscent of one worn by Padme Amidala in Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones; a Jedi temple guard mask such as the one once worn by the Grand Inquisitor, a character who appears in Rebels and Obi-Wan Kenobi; Sith and Jedi holocrons, featured in Rebels; the helmet of Galen Marek, aka Starkiller, worn by that character in the video game Star Wars: The Force Unleashed; a Gungen shield, as seen in Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace; and a stone tablet depicting the World Between the Worlds, a space that first appeared in Rebels and reappeared in Ahsoka.vi All of these artifacts, insofar as they are presented without the history in which they might otherwise participate, suggest magic and myth. There can be no question, however, of the type of image they present, of the type of nonnarrative in which they participate.

Figure 1

I shall return to this franchise image, its technical nature, and the tension it visualizes below. In order to better understand the stakes of this sort of image for Star Wars particularly and for the franchise form more generally—stakes having to do with the relation between myth, prehistory, and the traditional image, on one hand, and nonnarrative, posthistory, and the technical image on the other—we must address the question of history itself and the role history has played for Star Wars both contextually and textually.

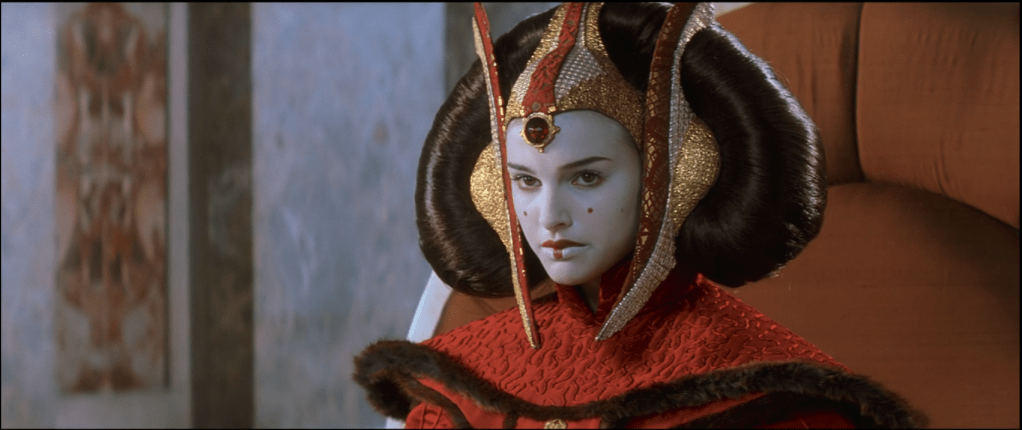

History stands opposed to myth in any number of ways. Whereas myth presents a relatively static world governed by objective codes, history represents a dynamic world through subjective interpretations of those codes. Myth presents “subjects” largely indistinguishable from objects insofar as they do not change of their own volition and insofar as they stand in for such objects, e.g. as Apollo stands in for the sun or Demeter for the earth. History opposes subjects to objects even as the actions of the former intervene into and create meaning out of the latter. Most importantly, whereas mythical objects present themselves as fully formed, outside of any human initiated process, historical objects emerge and develop under particular, determinate conditions by way of the action of the subject upon the world. To the extent that Star Wars presents itself as a mythopoetic antidote to the cynicism of the 1970s and the narratives thereof, it treats the various objects that populate its world as without history, claims about the “lived in” universe notwithstanding. Consider, for example, the hairstyle Princess Leia Organa wears in the film’s final scene (Figure 2). This scene presents a celebration of the destruction of the Death Star (which, according to the film’s mythopoetic logic, was never constructed, stolen plans notwithstanding). This celebration’s ritualistic nature suggests not the dynamics of history, according to which a hero who has been determined by historical circumstance has, through their subjective action, altered that historical circumstance (or failed to alter it by virtue of its recalcitrance). As ritual, this celebration imagines a universal and eternal image of the hero, a form of “subject” who transcends their historical situation and participates thereby in an objective, universal code (e.g. the hero’s journey, the triumph of good over evil) that reflects and anticipates past and future performances of precisely the same ritual. In this context, Leia’s hairstyle does not derive from a subjective sense of fashion or serve as a marker of self-identity but rather participates in an objective code according to which female ritualists, whose individual subjectivities are diminished and muted in the context of the ritual, conform to the standards of every other female ritualist, whether past, present, or future. Similarly, the headpieces and makeup Queen Padme Amidala and her stand-ins wear in ritualistic contexts in Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace relate every queen of Naboo to one another (Figure 3). In the words of Star Wars historian Kristin Baver, “Queen Amidala presented herself as the living symbol of Naboo. She wore the striking traditional makeup adopted by all the planet’s queens. This consisted of a white pallor with red accents and, in accordance with ancient custom, the scar of remembrance. This symbol of Naboo’s past suffering marked her lower lip.”vii

Figure 2

Figure 3

Such backstory aside, few, if any, of the objects that appear onscreen in Star Wars or the other five saga films that follow it are presented as being the products of particular, determinate conditions that cause these things, rather than other things, to emerge within the world. However, even if Padme’s ritual attire in The Phantom Menace affirms ritual, it nonetheless disrupts A New Hope’s mythopoesis by presenting a different ritual that, one assumes, derives from the particular cultural practices of Naboo (as opposed to the particular cultural practices of Alderaan or of the Rebel Alliance). The Phantom Menace, that is, suggests the historical contingency of these rituals. This contingency is further affirmed and developed in Andor through the figure of Leida Mothma, the daughter of Mon Mothma and Perrin Fertha. Leida, whose name unsubtly references “Leia,” celebrates the so-called “old ways” of her Chandrillan culture, but does so as a reaction to a particular set of circumstances, as a repudiation of her upbringing on Coruscant, surrounded by historical transformation and the constant novelty thereof. (Indeed, Leida’s birth in 18 BBY suggests that she was conceived around the same time that Order 66 was executed, connecting her emergence within the history of Star Wars to an important, transformative event in franchise history). In one of the final scene’s of Andor’s first season, Leida wears a traditional Chandrillan hairstyle as her parents introduce her to the son of Davo Sculdun. Sculdun, a Chandrillan banker who has agreed to launder money for Mon in exchange for this introduction, hopes this introduction will lead to a betrothal of the same sort that Mon and Perrin experienced at roughly the same age. In other words, Andor presents Leida Mothma’s hairstyle not as something that is this way and not another way by virtue of an objective code that has no origin and participates in no development. It presents this hairstyle, and Leida’s reasons for wearing it, as determined by her subjective interpretation of particular conditions. These conditions include: Leida’s reactionary cultural politics, the history of Chandrillan culture, the political dealings of this young woman’s mother, the desires of a rich and powerful person for more power, the ongoing erosion of the liberal state established by the Old Republic at the hands of the Empire, and so on. In so doing, and in a manner similar to what The Phantom Menace does by way of Padme’s headpiece and hairtsyle, Andor historicizes Leia’s hairstyle from Star Wars within the franchise narrative.

Figure 4

Star Wars’s internal history is no easier to order than its internal narrative, namely because history is itself a narrative, one often produced according to the various conventions of prose fiction and according to the interpretations of subjects who are subject to the force of that narrative.viii Given more conventional, i.e. modern, circumstances, this problem would reveal itself as badly posed. An historicist reading of Andor and/or Star Wars would situate its object within the historical circumstances that have determined it. Such a reading would reveal the problem of ordering Star Wars as an historical problem, as belonging to and deriving from determinate conditions. However, while we might still produce such readings, and while such readings may remain useful in some contexts, they do not and cannot address the franchise form. As discussed above, this form emerges within posthistory and operates according to a logic of the database, through the calculation of texts into technical images rather than according to the logic of narrative and the conceptualization of traditional images into texts. As such, instances of the franchise form: resist any attempt to historicize them, fail to produce or offer linear narratives (including internal histories), and thereby challenge and number of assumptions critics and scholars make about the historical analysis of texts.

Consider Fredric Jameson’s well-known reading of Star Wars as a nostalgia film. “What could that mean?” asks Jameson. He answers,

I presume we can agree that this is not a historical film about our own intergalactic past. Let me put it somewhat differently: one of the most important cultural experiences of the generations that grew up from the ’30s to the ’50s was the Saturday afternoon serial of the Buck Rogers type—alien villains, true American heroes, heroines in distress, the death ray or the doomsday box, and the cliffhanger at the end whose miraculous resolution was to be witnessed next Saturday afternoon. Star Wars reinvents this experience in the form of a pastiche: that is, there is no longer any point to a parody of such serials since they are long extinct. Star Wars, far from being a pointless satire of such now dead forms, satisfies a deep (might I even say repressed?) longing to experience them again: it is a complex object in which on some first level children and adolescents can take the adventures straight, while the adult public is able to gratify a deeper and more properly nostalgic desire to return to that older period and to live its strange old aesthetic artifacts through once again. This film is thus metonymically a historical or nostalgia film: unlike American Graffiti, it does not reinvent a picture of the past in its lived totality; rather, by reinventing the feel and shape of characteristic art objects of an older period (the serials), it seeks to reawaken a sense of the past associated with those objects.ix

With “Postmodernism and Consumer Society” (the essay in which this passage appears), Jameson offers an early exploration of postmodernism as a periodizing concept, as a means to designate what he would eventually call “the cultural logic of late capitalism” and characterize as involving a widespread inability to think historically.x In contrast to properly historicist fictions, which emphasize the differences between historical periods and the subjects thereof, Star Wars, and other nostalgia films such as Body Heat, draw certain aspects of the past into the present and thereby denude them of their historical character.xi As Jameson notes, Star Wars does not refer to an actual past but rather to the serial form George Lucas consumed as a child. While children in 1977 might have taken the adventures of Luke Skywalker seriously, adults, in Jameson’s reading, consumed those adventures nostalgically, as a way to recapture a sense of the past, rather than the past itself in its historical specificity. Furthermore, Jameson suggests that we cannot even read Star Wars’s use of the serial form’s components in terms of parody as parody implies a critique of the object being parodied, a demonstration of the original object’s strangeness or wrongness. There is no point in parodying a form, the serial, whose strangeness can no longer be understood by those who consume its appropriation by Star Wars in 1977, whose wrongness no longer registers within a world that has left that form behind. In short, Jameson historicizes Star Wars not by showing how it represents some historical event symbolically (e.g. how the battle between the rebels and the Empire symbolically encodes the battle between the Viet Cong and the United States during the Vietnam War) but by showing how its particular engagement with a dead media form derives from the determinate cultural condition called postmodernism.

This is a powerful reading of Star Wars based upon a powerful critical methodology. A further consideration of this methodology, however, will demonstrate its inadequacies in the present context. In an earlier work, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act, Jameson argues for and describes a method of analyzing narrative texts, such as novels, that allows the critic to discover the operations of history insofar as they are part and parcel of a society’s economic mode of production (i.e. feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and so on). This method begins with a text that is “more or less construed as coinciding with the individual literary work or utterance” and understands that text as the symbolic resolution of a material contradiction within society.xii At this level of analysis, Star Wars might be understood as resolving a contradiction inherent to modernity and to capitalism, namely the contradiction between stability and progress whereby the individual subject’s sense of self and world erode under the onslaught of the new. Marx and Engels argue that, in modern, capitalist society, “All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”xiii In the face of such transformations, Star Wars offers a fantasy of return, fulfills a desire for something familiar, something reminiscent of what, in hindsight, seems a simpler time. That it cannot actually produce that simpler time, that it can only represent such a time through a calculation (i.e. the solution to a problem achieved through a treatment of numbers, perhaps the highest form of abstraction) of concepts (e.g. myth as concept, the hero’s journey as concept, the serial form as concept, and so on) that evoke that time, is itself the product of history even as it adumbrates a posthistorical condition.

At the second level of analysis, Jameson understands the individual text of the first level to now participate in “the great collective and class discourses of which a text is little more than an individual parole or utterance.”xiv At this level of analysis, Star Wars exists as a discrete text in relation to other discrete texts—all of which participate in a single, antagonistic “conversation” within an oppositional class structure, such as that between those who own the means of production and those who work those means of production under capitalism. As a move in this conversation, Stars Wars might be understood as a final gasp of New Hollywood’s challenge the studio system.xv Here, the Empire represents classical Hollywood. The rebels, in turn, represent filmmakers such as Lucas, Scorsese, and Coppola who were, in the 1970s, disrupting Hollywood’s established production practices.xvi Insofar as Star Wars “sides” with the rebels against the Empire, the film as a whole represents a mostly coherent, individual utterance within this larger conversation. New Hollywood films such as Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Lucas’s American Graffiti told personal stories that stood in contrast to studio films such as Singin’ in the Rain and Ben-Hur. Star Wars itself, both as a film about Lucas’s nostalgia and as a film about Lucas himself (i.e. Luke = Lucas), should also be understood as such a personal film. New Hollywood films often employed actors who did not fit into Hollywood types, such as Jack Nicholson and Robert DeNiro, and thus further challenged the studio production model, whose contract system required the use and reuse of actors and combinations of actors across disparate films (e.g. Warner Bros.’s use of Humphrey Bogart, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre in The Maltese Falcon and in Casablanca). This practice led to a certain homogeneity among the films so produced, a sameness reflected in the Empire’s clean spaces, limited color schemes, and immaculately uniformed personnel. In contrast to the homogeneity of the Empire, the rebels are presented as somewhat disorganized, somewhat dirty, somewhat disheveled—as actual human beings, flaws and all, who operate both within and against a code shared with the Empire. This is not to say that Star Wars finally succeeds as clear or simple move in an ongoing discussion of class. As Will Brooker points out, Leia’s outfits and demeanor, for example, fit in more with the Empire than with the rebels.xvii Moreover, Star Wars became a blockbuster. As a blockbuster, the film played a role in transforming Hollywood production practices, but this transformation was of the sort identified by Marx and Engels. That is, the blockbuster represents a retrenchment of capitalist production through the dissolution of established practices and the implementation of new practices that serve capitalism rather than a challenge to such production. However, the fact that Star Wars, as an utterance within a larger conversation, does not finally mean in a clear and coherent fashion does not in any way undermine its status as such an utterance. The contradictory nature of this utterance only underscores its status as a postmodern film.

As he shifts his focus from the second level of analysis to the third, Jameson addresses the sort of tension just described. The very possibility of a discourse among discrete texts upon the nature of class relations assumes and requires a unified code (i.e. a metacode) according to which that discourse can take place. Such codes manifest contradictions within themselves, contradictions the critic can identify and develop through their reading of the discourse. However, “the inverse move is also possible, and such concrete semantic differences can on the contrary be focused in such a way that what emerges is rather the all-embracing unity of a single code which [antagonistic class positions] must share and which thus characterizes the larger unity of the social system.”xviii Thus the third level takes codes, the systems that produce codes, and the forms that express these codes as objects of analysis. Through their manifestation within form (i.e. within The Novel or The Film rather than in a novel or a film) across decades or even centuries, these systems provide an index of history in the most precise sense of the term, history understood as the movement within and across modes of production. Each mode of production has a dominant code even as every mode of production carries within it residues of past codes and anticipations of future ones. By attending to a given form as it emerges over time, the critic can identify the dominant codes at work within it as well as residual and anticipatory codes characteristic of other modes of production. As such the critic can begin to grasp the movement of history itself. At this level of analysis, whatever subversive power Star Wars imagined itself as possessing in the late 1970s largely disappears as its structural and formal elements (e.g. its deployment of the hero’s journey, its use of continuity editing, or its nostalgia for a non-existant past) align it with a normative tradition of American film going back to at least D.W. Griffith. Some American narrative films, such as Citizen Kane, knowingly challenged that position from within the Hollywood, but the more powerful challenges to it come from without, from, for example, other national film cultures, documentary film, and the avant garde. Non-American and non-narrative films have understood themselves a means to produce a Third Reich (as in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will), as participating in the creation of revolutionary subjectivity (as in Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera), and as a gateway to the unconscious (as in Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s Un chien Andalou), among other things—all of which question the status quo of liberal capitalism, whether in reactionary or revolutionary ways. Within this larger context, the sign system that dominates Star Wars might best be understood as being itself liberal, as representing a desire to challenge film production practices without transforming the underlying conditions of such practices, as representing an ideological desire for a more equitable capitalism.

As demonstrated by these brief readings of Star Wars, Jameson’s method of historical analysis works. However, even when it addresses form it relies upon assumptions about its object that we must not make with regard to the franchise form. Recall that, at the first level of analysis, the object of inquiry more or less coincides with “the individual literary work or utterance.” At the second level of analysis, the “text is little more than an individual parole or utterance.” Even at the third level, where Jameson avoids such language, we must understand that we may only grasp form through its individual instances, through discrete objects whose discreteness exists within an underlying sameness that allows for comparison and exchange, i.e. the form itself. That is, we cannot read the Novel, just as we cannot consume the Commodity. We may only read novels and attempt to conceptualize the Novel as form out of what we imagine the novel to be, just as we may consume commodities and conceptualize from them the Commodity form. In this respect, Jameson relies upon modern notions about subjects and objects (that they are individuals rather than dividuals) and about which universe he exists within (a universe of the one-dimensional, linear text and its concepts rather than the universe of the zero-dimensional, “pointal” technical image and its calculations).xix Even as he insists that, at each level, the critic rewrites the text under analysis—as the symbolic solution to a material contradiction, as an utterance in a larger discourse, as an instance of form—the results of these operations remain individual texts, graspable according to methodologies developed under the same conditions as the texts themselves, methodologies given to making the same assumptions as such texts about the nature of subjects and objects under those conditions. The franchise form challenges such assumptions, and those who make them, at every turn.

In other words, we can historicize Star Wars but we cannot historicize Star Wars. Even if the former’s boundaries are blurry—to the extent that it references and incorporates elements of the serials and films Lucas consumed—“Star Wars” (or “A New Hope”) does not generally cause confusion with regard to what it denotes. The latter, as should be clear, does. Does “Star Wars” refer to a single text? If so, we cannot precisely situate it in a particular year. As discussed, Star Wars was determined by the 1970s in which it was produced and released, a very different historical circumstance than the world in which Andor was produced and released determined as as it was by the long aftermath of 9/11 and the wars caused by the attacks on the World Trade Center, by the sub-prime mortgage crisis of 2008, by the election of Donald Trump in 2016 (and the related matters of Brexit and increasing autocracy worldwide), and a global pandemic starting in 2020. The code or codes that dominated the world of 2022 must be distinguished from those that dominated 1977. The codes of 1977 still imply and serve a desire for truth, even when they fail or when they understand such truth to be an obsolete concept, as in so many of the neo-noirs of the decade (e.g. Dirty Harry, The Long Goodbye, and Chinatown). By contrast the codes of the 2020s are untethered from any concept or hope for truth, based as they are in the calculation of concepts rather than in the conceptualization of traditional images. This untethering mirrors the manner in which Star Wars’s internal narrative constantly untethers itself from the material ground that Andor provides for it, by way of an amnesia I shall further discuss in chapter XXXX. Such untetherings speak to a posthistorical condition in which contents might be ordered and reordered without attention to a metanarrative or a shared code according to which they might be interpreted and judged.

Here we may return to Azuma and, in turn, to Luthen’s gallery and its calculation of the Star Wars database. Azuma summarizes Ōtsuka Ejii’s theorization of narrative consumption, which understands consumers to consume not so much the small narratives that make up a cultural object (such as the individual episodes of a long-running anime) but rather the system, or grand narrative that lies behind these small narratives and allows them to mean in a conventional sense. Consumers of narrative value “the settings and the worldview” provided by the grand narrative according to which small narratives operate. However, as Azuma notes, and in a manner similar to how we consume forms such as the Novel or the Film, we consume grand narratives only indirectly when we consume of the small narratives that participate in their shared sign systems hidden behind or beneath a surface comprising narrative elements. Writes Azuma, “In modernity it came to be thought that the purpose of scholarship was to clarify the structure of the hidden layer,” the very thing that Jameson seeks to do through his method of historical analysis.xx Under postmodernity (which might be better understood as “posthistory” in the present contextxxi), the assumption that narrative surface (small narratives) reflects narrative depth (the grand narrative) that scholars might, through ingenious methods, decode and explain, has collapsed. (As I shall discuss in chapter two, scholarship has not responded well to the new state of affairs.) This assumption comes to be replaced by another, namely that the “depth” behind small narratives, now understood as a database, “lacks any form of narrativity” and thus amounts to “a grand nonnarrative.”xxii

Just as there can be no question of what type of image the franchise form deploys, there can be no question of Star Wars and Andor’s nonnarrative status. Nonetheless, there remains among certain commentators, bound as they are to assumptions that derive from history and modernity, an assumption about the historical or even prehistorical nature of Star Wars and the images part and parcel of its (non)narrative. Luthen’s shop, the image of which emerges over several episodes of Andor, appears to imagine relations between objects, as being a traditional image. However, the traditional image begins with three-dimensional objects that have been abstracted from a four-dimensional world. It strips away one of those dimensions to imagine a relationship whose power of abstraction produces a relationship of resemblance and similarity among these objects and thus forestalls novelty. Again, the objects in Luthen’s shop may appear to enjoy this sort of relationship with one another, but this appearance is a residue of a past historical moment, one that lost its dominance when the human took a third step up the ladder of abstraction and began to conceptualize what it previously imagined. Thus Luthen’s shop might appear to participate in such conceptualization, to take an image of these artifacts that imagines their sameness (e.g. their belonging to the same universe) and, because that sameness no longer suffices to do away with novelty and the threats thereof, produce for them a new rectilinear relation called narrative. This narrative would, through its own power of abstraction, explain the artifacts in a way that a traditional image of them could not. And it is here that methodologies developed under historical conditions and subject to the assumptions thereof fail. The relationships among contents, among the elements of a technical image and of the Star Wars database, cannot be conceptualized, cannot be ordered into a rectilinear narrative, because contents are characterized by their dividuality, by their participation in manifold, contradictory relationships that afford manifold, contradictory orderings. Contents may participate in any number of small narratives, but those small narratives cannot be subordinated to a grand narrative . At best, the code called “grand narrative” exists as the residue of history and appears in the technical franchise image, alongside the imaginings of the traditional image, the camera movement, the characters, the props, the editing techniques, and so on as one more content that itself might participate in any number of small narratives.xxiii

One of the gallery’s artifacts, one that first appears in episode ten, “One Way Out,” illustrates the dynamic at work here. This artifact strongly resembles an elaborate headpiece worn by Padme Amidala in Attack of the Clones (Figures 5 and 6) during a scene in which she flees from Coruscant, in the company of Anakin Skywalker, after an attempt upon her life. No doubt this headpiece has a backstory similar to the one Baver provides for Padme’s makeup in The Phantom Menace but nonetheless distinct insofar as Padme wore that makeup (and a different, more elaborate headpiece) as queen but wears this headpiece as a senator. That she wears this headpiece in Anakin’s presence, as the two embark upon a journey that will result in their marriage and hence the birth of Luke and Leia (and the death of Padme and the rise of Darth Vader) relates the artifact to the main thread of the franchise narrative as it existed in 2001, when only five films existed. That it appears in a scene that emerges in the wake of political violence (the attempted assassination of Padme), also relates it to the “historical” conditions that, in part, determine the shape of that narrative. In this sense, the headpiece appears to participate in at least one small narrative (the cultural history of Naboo as it emerges across episodes I and II) and perhaps hints at an underlying grand narrative (the Skywalker saga) to which that small narrative is subordinate. However, even if such were the case in 2001, this ordering of Star Wars reveals its contingency as soon as it confronts the flood of shit (where “shit” connotes “unorderable information” or “contents” rather than an aesthetic or moral judgment) unleashed by Luscasfilm with Star Wars: The Clone Wars starting in 2008 and by Disney after its acquisition of Lucasfilm in 2012. At first glance, this surfeit of novelty seems to simply subordinate the small narrative of Padme’s headpieces and makeup to the grand narrative of Naboo’s history. However, it would be more accurate to say that, given the drive to expansion characteristic of the franchise form, Naboo’s history becomes, under the onslaught of this flood, just another content, albeit one that itself is spread across multiple other contents (i.e. films episodes of various series, novels, and so on). Just like any other content, the cultural history of Naboo invites and requires orderings into small narratives that never resolve, finally, into a unified grand narrative that might be interpreted in order to discover the operations of history hiding beneath its surface. Any attempt at constructing such a grand narrative will result in another content, whether that content appears in the Disney+ interface as a sanctioned ordering of other Star Wars content or remains forever in the head of the fan who calculated it.

Figure 5

Figure 6

The status of the headpiece is only further complicated by its appearance in Luthen’s gallery, a content that might be ordered with the saga films and thus connect Andor to aspects of Star Wars it otherwise seems to reject, namely the centering of the franchise narrative in the story of a single family’s profound influence on the course of that narrative. Likewise, it might be ordered, in the manner hinted at above, as part of Star Wars’s representation of women that, in the saga films up to and including Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, mainly understands them as smart and capable but nonetheless subordinate to and reliant upon men. Padme, Leia, and Leida have some control over their lives, but they nonetheless die insofar as they participate in a man’s narrative, are saved from death as part of a man’s narrative, and exert that control by adopting a reactionary cultural politics. Finally, the headpiece might be ordered with Andor itself and the concerns thereof. Does the headpiece, along with the other contents next to which it appears, suggest salvage, the identification and exploitation of value hidden within the shit left over from the past? Or does the gallery operate as a “place where time stands still” in a more mythical sense, as a place that collects what should no longer be understood as valuable? Does Luthen or Kleya know the provenance of the headpiece, know that it once belonged to someone who was deeply entangled in the process of producing the very world they now seek to transform? This last question raises two more, namely whether the headpiece in the gallery is the headpiece worm by Padme and whether the headpiece we see onscreen is the headpiece worn by Natalie Portman while shooting Attack of the Clones.

As should be clear, such questions as these have answers. However, they can never be answered even with the relative finality provided by modern, historicist modes of interpretation. The radical contingency of all meaning under posthistorical conditions becomes clear in the line that directly follows from Luthen Rael’s invitation to Mon Mothma to leave her troubles behind as she enters a place where time stands still: “It’s hard to be surrounded with this much history and not be humbled by the insignificance of our daily anxieties.” The irony of this line should not be missed as the contents of Luthen’s shop, as contents in the sense deployed here, do not participate in a grand narrative apposite historical existence. Insofar as they appear to be traditional images, images that emerge fully formed without a past condition that informs them, they gesture towards the prehistory and myth with which Star Wars and the saga films are so often associated. Again, however, this appearance is nothing but an appearance and these contents are technical images, as all franchise images must be, and thus participate in posthistory and nonnarrative to the extent that they remain unsubordinated to any final ordering principle, whether the four-dimensional, “natural” relations expressed by traditional images of three-dimensional objects or the conceptualized, one-dimensional relations expressed by writing about two-dimensional traditional images. The calculations through which the technical image emerges out of written history cannot be gathered up. We have no access to a further degree or level of abstraction through which such a task might be accomplished, a fact that points towards a second irony in Luthen’s claim, specifically that the daily anxieties that one might leave behind in a place where time stands still are precisely Andor’s focus, a focus that emerges by way of the “and/or” relationship between the series and the franchise of which it is part. Food, labor, sex, petty animosities, minor failures: so much of what is missing from Star Wars appears in Andor as sources of stress and conflict. In the context of the saga films and their depictions of the major victories and setbacks of the Rebel Alliance, these anxieties may indeed seem insignificant. At the same time, Andor demonstrates that such anxieties, and the day-to-day more generally, provide the condition upon which the narrative movements of the saga films might be grounded if only they might be subordinated to a grand narrative that would allow for such a grounding.

Kristin Baver begins her author’s note to Star Wars: 100 Objects: Illuminating Items From a Galaxy Far, Far Away with a statement about the power of “collections of artifacts” in museums to “recover people lost to time.” By invoking both the traditional image (the images created by prehistoric people) and writing (the historical conceptualizations of such images that allow for such recovery), Baver demonstrates her posthistorical status, her entanglement with a relationality I have described by way of the inclusive-exclusion “and/or,” a relationality that renders the tension among prehistory, history, and posthistory, as seen in a museum or in the franchise image of Luthen’s shop, as content by excluding from posthistory the functions of prehistorical and historical forms even as those forms are salvaged as contents. Baver goes on to compare what she has done in 100 Objects to the activities of those who produce such collections: “Within these pages, we have curated a collection of 100 items from each Star Wars era as seen on screen with the help and patient guidance of the archivists at Skywalker Ranch and the Lucasfilm archive.”xxiv Curation involves the ability to identify value, to see in an otherwise unordered artifact its virtual relationships, its relationality, with other such objects, relationality out of which a (small and contingent) narrative might be produced. Under the condition of posthistory, under the regime of the technical image, under the power of the database, such relationality is value, perhaps the only value we have left.

iSee lyotard

iiOn the incredulity towards metanarrative see The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Discuss here why Azuma misunderstands the word postnmodern While I would quibble with some of his assumptions about postmodernity and with some of his definitions of “grand narrative” and related terms, Azuma provides, in Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, a key text for understanding twenty-first-century cultural production as distinct from the forms such production took in earlier historical periods.

iiiVilém Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images, trans. Nancy Ann Roth (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 8.

ivFlusser, 7.

vFlusser, 13.

vihttps://www.starwars.com/news/andor-luthens-gallery-easter-eggs

viiKristin Baver, Star Wars 100 Objects: Illuminating Items from a Galaxy Far, Far Away (New York, NY: Dk Publishing, 2023), 50.

viiiSee Metahistory

ixFredric Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (New York: New Press, 1998), 116.

xSee Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991).

xiOn properly historicist fiction, see Lukacs. Interestingly, Jameson follows Lukacs in acknowledging that the historical novel had lost, by the late nineteenth century, its capacity to imagine how the past differs from the present. In this context, science fiction became a primary means by which cultural production could imagine difference, namely how the future would be different than the present in which it is produced. Star Wars refuses to think about difference at all, and thus cannot be considered science fiction according to this definition.

xiiFredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1981), 76.

xiiiKarl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Eric J. Hobsbawm, The Communist Manifesto: A Modern Edition (London: Verso, 1998), 38–39.

xivJameson, The Political Unconscious, 76. “Parole” is distinguished in French from langue. Whereas the latter refers to a language system, here the shared code that allows for the class antagonism Jameson describes, the former refers to a particular utterance made within that system, i.e. the individual novel that operates within that shared code

xvI take this sort of reading, in which the films of post-studio-system Hollywood allegorize the internal and external conflicts in which the studios had become entangled, from JD Conner.

xviSee stuff on New Hollywood.

xviiSee Will Brooker, Star Wars (London: Bloomsbury, 2020).

xviiiJameson, The Political Unconscious, 88.

xixI deal with these different forms of subjectivity in chapter three. For now, suffice it to say that I am relying here on Gilles Deleuze’s reading of Michel Foucault’s notion of discipline in Postscript. In that short essay, Deleuze engages with Discipline and Punish.

xxHiroki Azuma, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 31.

xxiIn order to avoid the confusion I alluded to in note XX I shall, after this chapter, refer to the contemporary historical period as postcapitalist or posthistorical rather than postmodern, reserving the latter term for use in particular engagements with other thinkers.

xxiiAzuma, Otaku, 38.

xxiiiThroughout this chapter, and here especially, I am indebted to Deleuze and Guattari’s discussion of the whole and its parts: “Hence Proust maintained that the whole itself is a product, produced as nothing more than a part alongside other parts, which it neither unifies nor totalizes, though it has an effect on these other parts simply because it establishes aberrant paths of communication between noncommunicating vessels, transverse unities between elements that retain all their differences within their own particular boundaries.” Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), 43.

xxivBaver, Star Wars 100 Objects, 7.

Leave a comment